Proof of impossibility

A proof of impossibility, sometimes called a negative proof or negative result, is a proof demonstrating that a particular problem cannot be solved, or cannot be solved in general. Often proofs of impossibility have put to rest decades or centuries of work attempting to find a solution. Proofs of impossibility are usually expressible as universal propositions in logic (see universal quantification).

One of the oldest and most famous proofs of impossibility was the 1882 proof of Ferdinand von Lindemann showing that the ancient problem of squaring the circle cannot be solved, because the number π is transcendental and only algebraic numbers can be constructed by compass and straightedge. Another classical problem was that of creating a general formula using radicals expressing the solution of a polynomial equation of degree 5 or higher. Galois showed this impossible using concepts such as solvable groups from Galois theory, a new subfield of abstract algebra that he conceived.

Among the most important proofs of impossibility of the 20th century were those related to undecidability, which showed that there are problems that cannot be solved in general by any algorithm at all. The most famous is the halting problem.

In computational complexity theory, techniques like relativization (see oracle machine) provide "weak" proofs of impossibility excluding certain proof techniques. Other techniques like proofs of completeness for a complexity class provide evidence for the difficulty of problems by showing them to be just as hard to solve as other known problems that have proven intractable.

The existence of irrational numbers: Pythagoras proof

Although not usually considered an "impossibility proof", the proof by Pythagoras or his students that the square-root of 2 cannot be expressed as the ratio of two integers (counting numbers) has had a profound effect on mathematics: it bifurcated "the numbers" into two non-overlapping collections—the rational numbers and the irrational numbers. This bifurcation was used by Cantor in his diagonal method, which in turn was used by Turing in his proof that the Entscheidungsproblem (the decision problem of Hilbert) is undecidable.

ca 500 B.C. "It is unknown when, or by whom, the 'theorem of Pythagoras' was discovered. 'The discovery', says Heath, 'can hardly have been made by Pythagoras himself, but it was certainly made in his school.' Pythagoras lived about 570-490. Democritus, born about 470, wrote 'on irrational lines and solids'...

Proofs followed for various square roots of the primes up to 17. "There is a famous passage in Plato's Theaetetus in which it is stated that Teodorus (Plato's teacher) proved the irrationality of

'taking all the separate cases up to the root of 17 square feet..." (Hardy and Wright, p. 42).

A more general proof now exists that:

- The mth root of an integer N is irrational, unless N is the mth power of an integer n" (Hardy and Wright, p. 40).

The existence of transcendental numbers

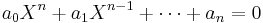

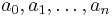

There exists at least one number for which it is impossible to find any algebraic equation that this number satisfies (i.e. you plug the number into the equation wherever X occurs and the equation equals zero). Stated another way: There exists at least one number which does not satisfy any equations of the form called an algebraic equation:

where  are integers, not all zero. Numbers that do not satisfy any equation of this form are called transcendental numbers.

are integers, not all zero. Numbers that do not satisfy any equation of this form are called transcendental numbers.

"It is not immediately obvious that there are any transcendental numbers, though actually, as we shall see in a moment, almost all real numbers are transcendental" (Hardy and Wright, p. 160)

Hardy and Wright (p. 160) offer theorems to show that:

- The aggregate of algebraic numbers is enumerable.

- Almost all real numbers are transcendental.

- A real algebraic number of degree n is not approximable to any order greater than n (Liouville's theorem)

This last theorem "enables us to produce as many examples of transcendental numbers as we please" (Hardy and Wright p. 161).

Hardy and Wright go on to prove that pi and the "exponential" e are transcendental. Hermite offered the first proof that e is transcendental (cf Notes in Hardy and Wright p. 177).

In a footnote p. 190 Hardy and Wright discuss the diagonal method of Cantor that demonstrates the existence of transcendental numbers.

Three impossible constructions

Three famous questions of Greek geometry were:

- "...with compass and straight-edge to trisect any angle,

- to construct a cube with a volume twice the volume of a given cube, and

- to construct a square equal in area to that of a given circle.

For more than 2,000 years unsuccessful attempts were made to solve these problems; at last, in the nineteenth century it was proved that the desired constructions are logically impossible" (Nagel and Newman p. 8).

Squaring the circle requires transcendental numbers, unattainable by compass and straightedge. Both doubling the cube and trisecting the angle require third roots, which are not constructible numbers by compass and straightedge.

"Pi is not a 'Euclidean' number ... and therefore it is impossible to construct, by Euclidean methods a length equal to the circumference of a circle of unit diameter" (Hardy and Wright p. 176)

A Euclidean number is one which can be constructed by use of a straight-edge and compass. (Hardy and Wright p. 159). Irrational numbers can be Euclidean. A good example is the irrational number: square-root of 2. It is simply the length of the hypotenuse of a right triangle. We can produce this length as follows:

- With the straight-edge draw a line

- Bisect it with the compass

- Draw the perpendicular through the line

- With the straight edge draw a "unit distance"

- Use the compass to span (measure) the unit distance

- Span (measure), on each "leg" of the right angle, the "unit distance"

- Draw the hypotenuse through these end-points

The hypotenuse has the length square-root of 2 (times the unit distance)

A proof exists to demonstrate that any Euclidean number is an algebraic number. Therefore, because pi is a transcendental number then, by definition, it is not an algebraic number, and therefore it is not a Euclidean number as well. Thus the construction of a pi-length from a unit circle is impossible. [Hardy and Wright p. 159 reference E. Hecke Vorlesungen über die Theorie der algebraischen Zahlen (Leipzig, Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft, 1923].

Euclid's parallel axiom

Nagel and Newman consider the question raised by the parallel postulate to be "...perhaps the most significant development in its long-range effects upon subsequent mathematical history" (p. 9).

The question is: can the axiom that two parallel lines "...will not meet even 'at infinity'" (footnote, ibid) be derived from the other axioms of Euclid's geometry? It was not until work in the nineteenth century by "... Gauss, Bolyai, Lobachevsky, and Riemann, that the impossibility of deducing the parallel axiom from the others was demonstrated. This outcome was of the greatest intellectual importance. ...a proof can be given of the impossibility of proving certain propositions within a given system" (p. 10).

To clarify: Nage and Newman mean "the proposition" to be the statement "Parallel lines will not meet at infinity" and "the given system" is Euclid's axioms of geometry. The proof showed that no proof exists; i.e. "a proof" is impossible.

Richard's paradox

This profound paradox presented by Jules Richard in 1905 informed the work of Kurt Gödel (cf Nagel and Newman p. 60ff) and Alan Turing. A succinct definition is found in Principia Mathematica:

- "Richard's paradox... is as follows. Consider all decimals that can be defined by means of a finite number of words [boldface added for emphasis, "words" are symbols]; let E be the class of such decimals. Then E has [aleph-sub-zero-- an infinity of] terms; hence its members can be ordered as the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, ... Let N be a number defined as follows [Whitehead & Russell now employ the Cantor diagonal method]; If the nth figure in the nth decimal is p, let the nth figure in N be p+1 (or 0, if p = 9). Then N is different from all the members of E, since, whatever finite value n may have, the nth figure in N is different from the nth figure in the nth of the decimals composing E, and therefore N is different from the nth decimal. Nevertheless we have defined N in a finite number of words [i.e. this very word-definition just above!] and therefore N ought to be a member of E. Thus N both is and is not a member of E" (Principia Mathematica, 2nd edition 1927, p. 61).

Kurt Gödel considered his proof to be "an analogy" of Richard's paradox (he called it "Richard's antinomy") (Gödel in Undecidable, p. 9). See more below about Gödel's proof.

Alan Turing constructed this paradox with a machine and proved that this machine could not answer a simple question: will this machine be able to determine if any machine (including itself) will become trapped in an unproductive "infinite loop" (i.e. it fails to continue its computation of the diagonal number).

Can this proof be "decided" on the basis of the axioms? Gödel's proof

To quote Nagel and Newman (p. 68), “Gödel’s paper is difficult. Forty-six preliminary definitions, together with several important preliminary theorems, must be mastered before the main results are reached” (p. 68). In fact, Nagel and Newman required a 67-page introduction to their exposition of the proof. But if the reader feels strong enough to tackle the paper, Martin Davis observes that “This remarkable paper is not only an intellectual landmark, but is written with a clarity and vigor that makes it a pleasure to read” (Davis in Undecidable, p. 4). It is recommended that most readers see Nagel and Newman first.

So what did Gödel prove? In his own words:

- “It is reasonable… to make the conjecture that ...[the] axioms [from Principia Mathematica and Peano ] are ... sufficient to decide all mathematical questions which can be formally expressed in the given systems. In what follows it will be shown that this is not the case, but rather that ... there exist relatively simple problems of the theory of ordinary whole numbers which cannot be decided on the basis of the axioms” (Gödel in Undecidable, p. 4).

Gödel compared his proof to “Richard’s antinomy” (an "antinomy" is a contradiction or a paradox; for more see Richard's paradox):

- “The analogy of this result with Richard’s antinomy is immediately evident; there is also a close relationship [14] with the Liar Paradox (Gödel's footnote 14: Every epistemological antinomy can be used for a similar proof of undecidability)... Thus we have a proposition before us which asserts its own unprovability [15]. (His footnote 15: Contrary to appearances, such a proposition is not circular, for, to begin with, it asserts the unprovability of a quite definite formula)" (Gödel in Undecidable, p.9).

Will this computing machine lock in a "circle"? Turing's first proof

- The Entscheidungsproblem, the decision problem, was first answered by Church in April 1935 and preempted Turing by over a year, as Turing's paper was received for publication in May 1936. (Also received for publication in 1936—in October, later than Turing's—was a short paper by Emil Post that discussed the reduction of an algorithm to a simple machine-like "method" very similar to Turing's computing machine model (see Post-Turing machine for details).

- Turing's proof is made difficult by number of definitions required and its subtle nature. See Turing machine and Turing's proof for details.

- Turing's first proof (of three) follows the schema of Richard's Paradox: Turing's computing machine is an algorithm represented by a string of seven letters in a "computing machine". Its "computation" is to test all computing machines (including itself) for "circles", and form a diagonal number from the computations of the non-circular or "successful" computing machines. It does this, starting in sequence from 1, by converting the numbers (base 8) into strings of seven letters to test. When it arrives at its own number, it creates its own letter-string. It decides it is the letter-string of a successful machine, but when it tries to do this machine's (its own) computation it locks in a circle and can't continue. Thus we have arrived at Richard's paradox. (If you are bewildered see Turing's proof for more).

A number of similar undecidability proofs appeared soon before and after Turing's proof:

- April 1935: Proof of Alonzo Church (An Unsolvable Problem of Elementary Number Theory). His proof was to "...propose a definition of effective calculability ... and to show, by means of an example, that not every problem of this class is solvable" (Undecidable p. 90))

- 1946: Post correspondence problem (cf Hopcroft and Ullman p. 193ff, p. 407 for the reference)

- April 1947: Proof of Emil Post (Recursive Unsolvability of a Problem of Thue) (Undecidable p. 293). This has since become known as "The Word problem of Thue" or "Thue's Word Problem" (Axel Thue proposed this problem in a paper of 1914 (cf References to Post's paper in Undecidable, p. 303).

- Rice's theorem: a generalized formulation of Turing's second theorem (cf Hopcroft and Ullman p. 185ff)[1]

- Greibach's theorem: undecidability in language theory (cf Hopcroft and Ullman p. 205ff and reference on p. 401 ibid: Greibach [1963] "The undecidability of the ambiguity problem for minimal lineal grammars," Information and Control 6:2, 117-125, also reference on p. 402 ibid: Greibach [1968] "A note on undecidable properties of formal languages", Math Systems Theory 2:1, 1-6.)

- Penrose tiling questions

- Question of solutions for Diophantine equations and the resultant answer in the MRDP Theorem; see entry below.

The fundamental theorem of arithmetic

Gödel used these theorems in his proof (see below, more in Nagel and Newman p. 68). He figured out a way to express any mathematical formula or proof (in arithmetic) as a product of prime numbers raised to powers. And because he could factor any number into its unique primes, he was able to recover a formula or proof intact from its number by factoring it.

A prime number is defined as a counting number that is divisible only by itself and 1.

First theorem (cf Hardy and Wright, p. 2):

- "Every positive integer (counting number), except 1, is a product of primes" OR Excepting 1, it is impossible to find a positive integer that is not a product of primes.

Second theorem: fundamental theorem of arithmetic (cf Hardy and Wright p. 3):

- Every integer (counting number) has a unique expression as a product of primes. OR: It is impossible to factor an integer into primes in more than one way. (This does not include "permutations" of the primes).

Thus, if we pick a number e.g. 85, we see that it has prime factors 5 and 17, and this is unique (85 = 5×17 or 17×5), or 8 = 2×2×2 = 23.

Neither proof is particularly trivial. Hardy and Wright attribute an explicit statement of the Fundamental Theorem to Gauss. "It was, of course, familiar to earlier mathematicians" (Hardy and Wright, p. 10).

Is this string of 1's and 0's random? Chaitin's proof

For an exposition suitable for non-specialists see Beltrami p. 108ff. Also see Franzen Chapter 8 pp. 137–148, and Davis p. 263-266. Franzén's discussion is significantly more complicated than Beltrami's and delves into Ω -- Gregory Chaitin's so-called "halting probability". Davis's older treatment approaches the question from a Turing machine viewpoint. Chaitin has written a number of books about his endeavors and the subsequent philosophic and mathematical fallout from them.

- "A paraphrase of Chaitin's result is that there can be no formal proof that a sufficiently long string is random..." (Beltrami p. 109)

Beltrami observes that "Chaitin's proof is related to a paradox posed by Oxford librarian G. Berry early in the twentieth century that asks for 'the smallest positive integer than cannot be defined by an English sentence with fewer than 1000 characters.' Evidently, the shortest definition of this number must have at least 1000 characters. However, the sentence within quotation marks, which is itself a definition of the alleged number is less than 1000 characters in length!" (Beltrami, p. 108)

Does this Diophantine equation have an integer solution? Hilbert's tenth problem

For reference until this entry can be better constructed see Franzén pages 70–71.

This problem is related to Fermat's last theorem, only recently proved by Andrew Wiles (1994). Previously in his book (p. 10, 11) Franzén describes what a Diophantine equation is and gives good examples (Fermat's last theorem has to do with a simple type of Diophantine equation recognizable to students as part of the conclusion of the Pythagorean theorem when the exponent is "2").

- Question: Does any arbitrary "Diophantine equation" have an integer solution? Answer: undecidable.

- Fermat's last theorem: "No equation of the form

- xn + yn = zn with n greater than 2 have any solution in positive integers" (Franzén p. 11)

Franzén introduces "Hilbert's 10nth problem" and the MRDP theorem (Matiyasevich-Robinson-Davis-Putnam theorem) which states that no algorithm exists which can decide whether or not a Diophantine equation has any solution at all. Franzén's treatment is a creditable job but relies on the reader's understanding of certain terminology with reference to Turing's theorem that he develops a few pages beforehand: MRDP uses the undecidability proof of Turing: "... the set of solvable Diophantine equations is an example of a computably enumerable but not decidable set, and the set of unsolvable Diophantine equations is not computably enumerable" (p. 71).

Franzén also introduces a really fun unsolved problem, very easy to describe—even an elementary-algebra student in junior high could get the question: the Collatz conjecture (3n + 1 conjecture, Ulam's problem). That something so easy to describe and fun to fiddle with is unsolved is rather shocking! (Franzén, p. 11).

Is this simple question impossible to prove? The Collatz (3n + 1) conjecture

Also called Ulam's problem.

The entries above have now equipped the reader with the tools to think about an unsolved problem. Here's a chance to become famous:

- "No proof of the Collatz conjecture has been found in spite of intense efforts, and the problem is generally considered extremely difficult" (Franzen, p. 11).

This is Franzen's description of the problem:

- "... if we start with any positive natural number n and compute n/2 if n is even, or 3n + 1 if n is odd, and continue applying the same rule to the new number, we will eventually reach 1" (Franzén, p. 11)

Here are the first numbers. Clearly once certain numbers appear inside a string then they don't need to be "dealt with". But the lengths of the strings are interesting—they have a randomness to them that is "worrisome", per Chaitin's proof described above. This should lead us to believe that the question is "undecidable" (i.e. it's impossible to know whether the hypothesis is true or false):

- 1, 4, 2, 1

- 2, 1

- 3, 10, 5, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1

- 4, 2, 1

- 5, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1

- 6, 3, 10, 5, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1

- 7, 22, 11, 34, 17, 52, 26, 13, 40, 20, 10, 5, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1

- 8, 4, 2, 1

- 9, 28, 14, 7, 22, 11, 34, 17, 52, 26, 13, 40, 20, 10, 5, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1

- 10, 5, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1

- 11, 34, 17, 52, 26, 13, 40, 20, 10, 5, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1

- 12, 6, 3, 10, 5, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1

- 13, 40, 20, 10, 5, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1

- 14, 7, 22, 11, 34, 17, 52, 26, 13, 40, 20, 10, 5, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1

- 15, 46, 23, 70, 35, 106, 53, 160, 80, 40, 20, 10, 5, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1

- 80, 40, 20, 10, 5, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1

- 81, 244, 122, 61, 184, 92, 46, 23, 70, 35, 106, 53, 160, 80, 40, 20, 10, 5, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1

- 82, 41, 124, 62, 31, 94, 47, 142, 71, 214, 107, 322, 161, 484, 242, 121, 364, 182, 91, 274, 137, 412, 206, 103, 310, 155, 466, 233, 700, 350, 175, 526, 263, 790, 395, 1186, 593, 1780, 890, 445, 1336, 668, 334, 167, 502, 251, 754, 377, 1132, 566, 283, 850, 425, 1276, 638, 319, 958, 479, 1438, 719, 2158, 1079, 3238, 1619, 4858, 2429, 7288, 3644, 1822, 911, 2734, 1367, 4102, 2051, 6154, 3077, 9232, 4616, 2308, 1154, 577, 1732, 866, 433, 1300, 650, 325, 976, 488, 244, 122, 61, 184, 92, 46, 23, 70, 35, 106, 53, 160, 80, 40, 20, 10, 5, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1

But here's another clue that leads us to believe that the conjecture is true: algorithms that construct numbers are sometimes thought of as "proofs" in an axiom schema. For example, "proof" in number theory has a very precise meaning—that the next "provable formula" follows from either (i) an axiom, (ii) one prior "provable formula" or, (iii) two prior "provable formulas". In order to do these proofs in the framework of a tiny set of axioms, we might think of the numbers (and the formulas themselves) as strings of "unary", just "tally marks", separated by a "blank" symbol i.e. number "7" is | | | | | | |, i.e. 7 marks. If a proof is "true" then it is a tautology. Thus the statement "3 + 4 = 7" is a tautology i.e. | | | + | | | | = | | | | | | |. (To do this we would have to express the "+" symbol and "=" symbols in a similar code, and provide adequate "formation rules" etc.) If we "check the proof" (as we used to do in geometry) by writing down all the steps that led us to the end of the proof, then the proof always ends in "True". If we assign the symbol "1" as equivalent to "True" then whenever we proof-check a tautology it always ends in 1, just as the Collatz sequence does above.

Here's another clue that points to impossibility: we can describe a "machine" to do the computation as a "state machine". When the end-number is "1" then the machine halts (this is easy to construct). State machines are "destructive" of information in the sense that we can't trace backward what they did, or exactly what path they took to arrive at where they are (unless we record all their moves). You can see that in the sequences above. If the state machine is working on "20", how did it get to "20"? We need a Turing machine to tell us.

But another argument for a proof says "how could it be otherwise?" The only possibility would be that, somehow, the number just begins to increase to infinity. Is this plausible?

And yet we know that for slightly-modified forms of the problem such as { 5*N+3, N/2 } certain numbers fall into never-ending loops. Might there be some number really big N in the { 3*N+1, N/2 } problem that also results in a loop (actually 1 --> 4 --> 2 --> 1 is how the 3*N+1 problem actually ends up if the algorithm isn't halted at 1).

Notes

- ^ "...there can be no machine E which ... will determine whether M [an arbitrary machine] ever prints a given symbol (0 say)" (Undecidable p 134). Turing makes an odd assertion at the end of this proof that sounds remarkably like Rice's Theorem:

- "...each of these "general process" problems can be expressed as a problem concerning a general process for determining whether a given integer n has a property G(n)... and this is equivalent to computing a number whose nth figure is 1 if G(n) is true and 0 if it is false" (Undecidable p 134). Unfortunately he doesn't clarify the point further, and the reader is left confused.

References

- G. H. Hardy and E. M. Wright, An Introduction to the Theory of Numbers, Fifth Edition, Clarendon Press, Oxford England, 1979, reprinted 2000 with General Index (first edition: 1938). The proofs that e and pi are transcendental are not trivial, but a mathematically-adept reader will be able to wade through them.

- Alfred North Whitehead and Bertrand Russell, Principia Mathematica to *56, Cambridge at the University Press, 1962, reprint of 2nd edition 1927, first edition 1913. Chap. 2.I. "The Vicious-Circle Principle" p. 37ff, and Chap. 2.VIII. "The Contradictions" p. 60ff.

- Turing, A.M. (1936), "On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem", Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, 2 42 (1): 230–65, 1937, doi:10.1112/plms/s2-42.1.230 (and Turing, A.M. (1938), "On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem: A correction", Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, 2 43 (6): 544–6, 1937, doi:10.1112/plms/s2-43.6.544). online version This is the epochal paper where Turing defines Turing machines and shows that it (as well as the Entscheidungsproblem) is unsolvable.

- Martin Davis, The Undecidable, Basic Papers on Undecidable Propositions, Unsolvable Problems And Computable Functions, Raven Press, New York, 1965. Turing's paper is #3 in this volume. Papers include those by Godel, Church, Rosser, Kleene, and Post.

- Martin Davis's chapter "What is a Computation" in Lynn Arthur Steen's Mathematics Today, 1978, Vintage Books Edition, New York, 1980. His chapter describes Turing machines in the terms of the simpler Post-Turing Machine, then proceeds onward with descriptions of Turing's first proof and Chaitin's contributions.

- Andrew Hodges, Alan Turing: The Engima, Simon and Schuster, New York. Cf Chapter "The Spirit of Truth" for a history leading to, and a discussion of, his proof.

- Hans Reichenbach, Elements of Symbolic Logic, Dover Publications Inc., New York, 1947. A reference often cited by other authors.

- Ernest Nagel and James Newman, Gödel's Proof, New York University Press, 1958.

- Edward Beltrami, What is Random? Chance and Order in Mathematics and Life, Springer-Verlag New York, Inc., 1999.

- Torkel Franzén, Godel's Theorem, An Incomplete Guide to Its Use and Abuse, A.K. Peters, Wellesley Mass, 2005. A recent take on Gödel's Theorems and the abuses thereof. Not so simple a read as the author believes it is. Franzén's (blurry) discussion of Turing's 3rd proof is useful because of his attempts to clarify terminology. Offers discussions of Freeman Dyson's, Stephen Hawking's, Roger Penrose's and Gregory Chaitin's arguments (among others) that use Gödel's theorems, and useful criticism of some philosophic and metaphysical Gödel-inspired dreck that he's found on the web.